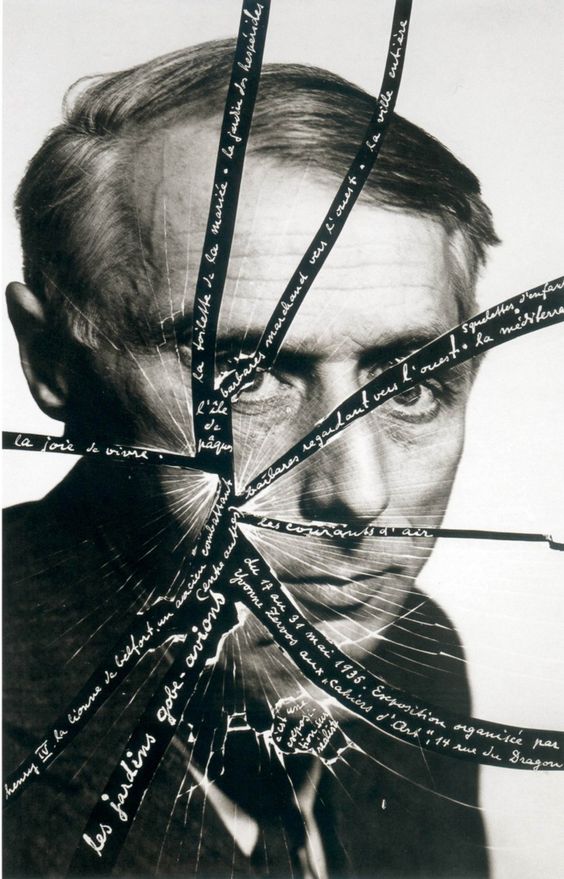

In 1936 the painter and art dealer Roland Penrose (also later the husband of Lee Miller) and the art critic Herbert Read, who were organising the International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries, decided to pay a visit to the studios of the Irish born painter Francis Bacon in Chelsea. Bacon showed them four large canvases but the visitors were underwhelmed, to say the least. Penrose declared that they were insufficiently surreal to be included and is reported to have told Francis, “Mr. Bacon, don’t you realise a lot has happened in painting since the Impressionists?”.

However much this must have stung, Francis Bacon apparently agreed with Penrose’s assessment as he would later, when very famous, ruthlessly suppress any pieces that pre-dated his breakthrough painting Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion of 1944; that is to say, that any painting produced before he had engaged, assimilated and felt in a position to response in a highly personal way to the great Continental European avant-garde currents (including, naturally enough, Surrealism), were to be excluded from his oeuvre. Quite rightly so, as the critic John Russell noted, “there was painting in England before the Three Studies, and painting after them, and no one…can confuse the two,” which of course extended to Bacon’s own work.

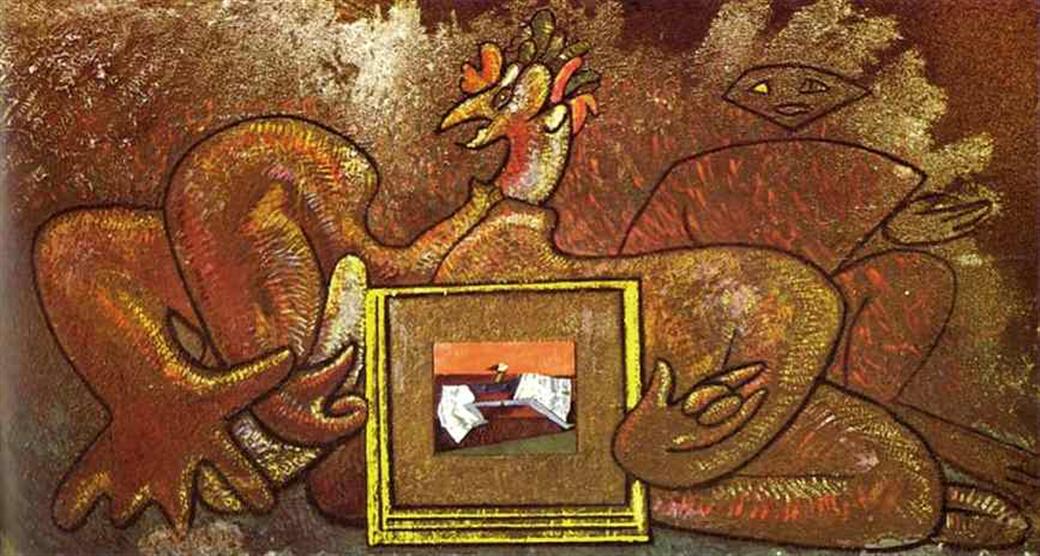

Painted on Sundeala boards, a cheap alternative to canvas, used frequently by Bacon as he was often short of money due to his heavy drinking and lifelong gambling habit, Three Studies presents three nightmarish figures, Bacon’s horror take on Picasso’s biomorphs, with elongated necks and distended mouths, against a lurid, harsh, burnt orange background. Christ and the two thieves crucified have been transformed into the Furies. Bacon admitted to having been obsessed by the phrase in Aeschylus, “the reek of human blood smiles out at me”, and in a sense Three Studies is a raw, visceral, pictorial actualisation of such a striking and terrifying line. After all, Bacon was the best exemplifier of the Bataillean aesthetic in the visual arts; the body as meat, the world as an abattoir, the endless scream of being.

![birds-also-birds-fish-snake-and-scarecrow[1]](https://cakeordeathsite.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/birds-also-birds-fish-snake-and-scarecrow1.jpg?w=800&h=747)

![Diego_Velaquez_Venus_at_Her_Mirror_The_Rokeby_Venus[1]](https://cakeordeathsite.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/800px-diego_velaquez_venus_at_her_mirror_the_rokeby_venus1.jpg?w=656)