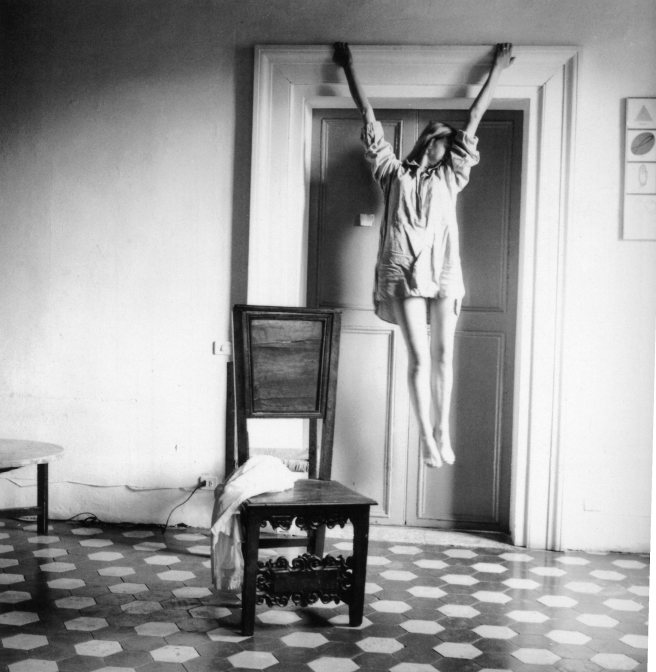

Lee Miller-Man Ray 1929

Lee Miller-Man Ray 1929

Robert Desnos was in many ways the archetypal surrealist spirit. Involved in Paris Dada he was in the literary vanguard of Surrealism and possessed an extra-ordinary talent for automatic writing during the Trance Period, rivalled only by Rene Crevel. Desnos, like many others, fell out with Andre Breton and joined the group centred around Georges Bataille and his magazine Documents and he was one of the signers of the anti-Breton polemic Un Cadavre.

During WWII Desnos was an active member of the French Resistance and he was captured by the Gestapo in 1944. He was deported to Auschwitz, then Buchenwald and finally Theresienstadt where he would die a few weeks after the camp’s liberation from typhoid.

I Have So Often Dreamed Of You

I have so often dreamed of you that you become unreal.

Is it still time enough to reach that living body and to kiss

on that mouth the birth of the voice so dear to me?

I have so often dreamed of you that my arms used as they are

to meet on my breast in embracing your shadow would

perhaps not fit the contour of your body.

And, before the real appearance of what has haunted and ruled

me for days and years, I might become only a shadow.

Oh the weighing of sentiment,

I have so often dreamed of you that there is probably no time

now to waken. I sleep standing, my body exposed to all the

appearances of life and love and you, who alone still

matter to me, I could less easily touch your forehead and

your lips than the first lips and the first forehead I

might meet by chance.

I have so often dreamed of you, walked, spoken, slept with your

phantom that perhaps I can be nothing any longer than a

phantom among phantoms and a hundred times more shadow

than the shadow which walks and will walk joyously over

the sundial of your life.

Translation Mary Ann Caws

![Francis-Picabia-The-woman-and-the-idol[1] Francis-Picabia-The-woman-and-the-idol[1]](https://cakeordeathsite.files.wordpress.com/2019/01/Francis-Picabia-The-woman-and-the-idol1.jpg?w=157&resize=157%2C229&h=229#038;h=229)

![two-women-with-poppies-1944_painter-francis-picabia[1] Francis Picabia-Two Women with Poppies 1944](https://cakeordeathsite.files.wordpress.com/2019/01/two-women-with-poppies-1944_painter-francis-picabia1.jpg?w=208&resize=208%2C292&h=292#038;h=292)