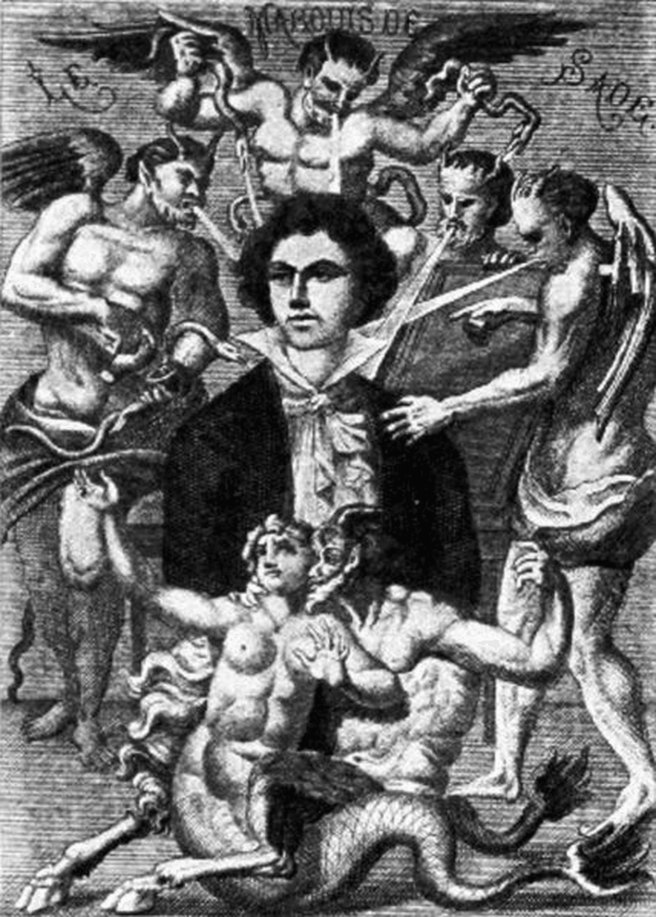

J.G Ballard once noted that the Marquis De Sade remains the spectre at the feast of European letters and thought. On the rare occasions when anyone decides to let him in from the cold, he leaves bloody footprints on the welcome mat.

A fiercely contrarian spirit, the Marquis has been variously called, by admirers and detractors alike: revolutionary, radical, reactionary, an anarchist, a socialist. Depending on who you read he is either a much maligned libertarian or he paved the theoretical way for the homicidal tyrants of the 20th century. No one can quite decide where the Marquis lies on the political spectrum. The debate is probably fiercest regarding his views on gender and pornography, understandably so as the body in De Sade is always the locus of power and freedom, but even here views diverge. Virulent misogynist whose fiction continually degrade and devalue women, or a radical feminist who, in one of his darkest fictions, Juliette, shows the possibility of complete female emancipation?

Illumination cannot be found in his life either. Strangely enough for a man who is know for transgression and excess, his behaviour as a free citizen in Republican Paris shows an unexpected moderation. De Sade didn’t avail himself of the unique opportunities present during the Terror, instead he kept a cool head while others were losing theirs.

After his release from prison in 1790 he lived in Paris with his mistress Marie Constant Quesnet and her six year old son. His long suffering wife Renee-Pelagie, after standing by him during the long years of imprisonment had obtained a divorce by this time. De Sade was elected to the National Convention and was appointed to the local Section Des Piques, one of the forty eight administrative divisions in the new Republic. It was in this position that he could have condemned his loathed in-laws, especially his mother-in-law, La Presidente who was responsible for the lettres de cachet that had caused him to be under lock and key for over a decade, to death. But he refrained; the Marquis De Sade had always been a principled opponent of the death penalty. This restraint and his criticism of Robespierre led to the Marquis being detained again in 1793, where he narrowly escaped execution due to a clerical error.

De Sade wrote a number of stirring pamphlets in defence of the Revolution, notably the famous Yet another effort, Frenchman, if you would become Republicans, nestled in his libertine classic La philosophie dans le boudoir (Philosophy in the Bedroom). In this text De Sade gives an outline of his version of Utopia, a minimal state that interferes as little as possible with the rights of the individual. I shall by reviewing this work in greater depth and further detail in the next post on the Marquis.