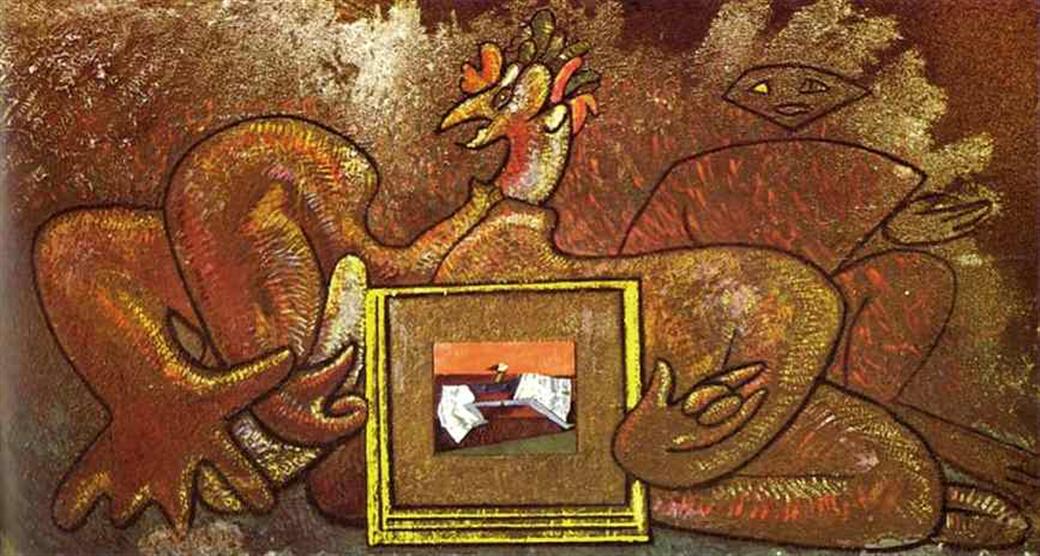

The German Surrealist Max Ernst was one of the most outstanding artists and personalities of the Surrealist movement. Notable for the invention of a number of automatic artistic techniques, his body of work is also remarkable for its creation of a densely rich personal mythology.

Central to that mythology is Ernst’s alter ego, Loplop, Superior of Birds. As I noted in my previous post A Week of Max Ernst: Monday, Ernst wrote that he hatched from an egg which his mother had laid in an eagle’s nest. He traced the figure of Loplop to a traumatic childhood event: his beloved pet bird had died on the same day that his younger sister was born and he consequently conflated the two events to the point that he confused birds with humans.

As well as referencing Freudian psychoanalytic theory, Ernst, whose art is drenched in alchemy and esotericism, would surely have been familiar with the idea of the language of the birds; the perfect, divine language found in mythology and the occult sciences that can only be understood by the initiated.

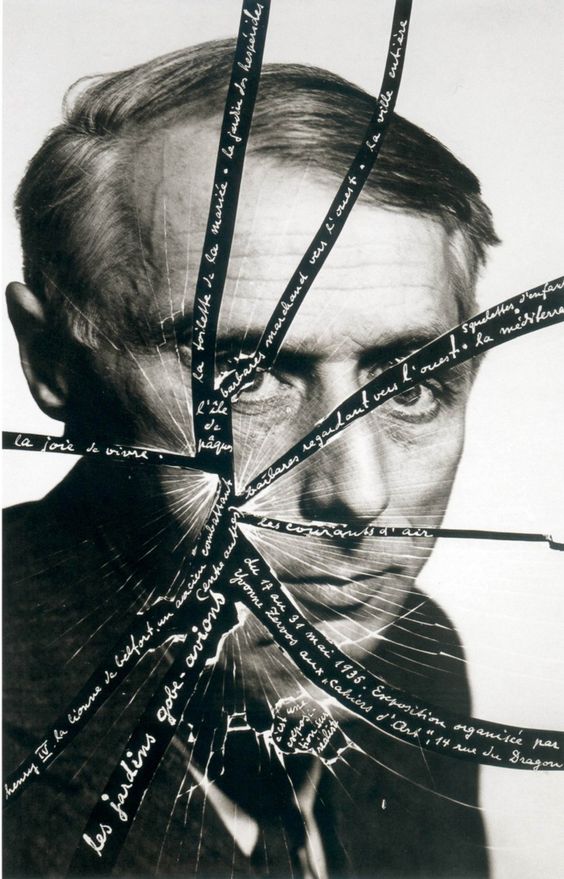

Loplop first appeared in his ground-breaking collage novels La Femme 100 Têtes and Une semaine de bonté. Birds are a recurring feature in Ernst’s artwork in various media (see A Week of Max Ernst: Tuesday, A Week of Max Ernst: Thursday & A Week of Max Ernst: Friday). I have also included a photo of Ernst’s striking, and it has to be admitted, birdlike visage.

![birds-also-birds-fish-snake-and-scarecrow[1]](https://cakeordeathsite.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/birds-also-birds-fish-snake-and-scarecrow1.jpg?w=800&h=747)

![of-this-men-shall-know-nothing-1923[1]](https://cakeordeathsite.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/of-this-men-shall-know-nothing-19231.jpg?w=656)